News

Department of Systems Biology Opens New Biotechnology Development Hub

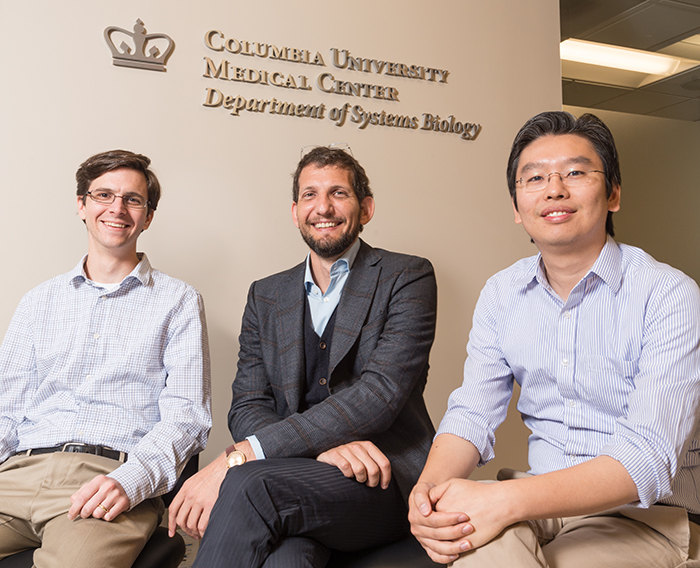

Assistant Professors Peter Sims, Sagi Shapira, and Harris Wang recently moved into a new Department of Systems Biology laboratory space designed to facilitate the development of new technologies for biological and biomedical research. Photo: Lynn Saville.

The Columbia University Department of Systems Biology has opened a new experimental research hub focused on biotechnology development. Occupying one and a half floors in the Mary Woodard Lasker Biomedical Research Building at Columbia University Medical Center, the facility will promote the design and implementation of new experimental methods for the study and engineering of biological systems. It will also enable a substantial expansion of Columbia’s next-generation genome sequencing capabilities.

The first occupants of the new facility are the laboratories of Department of Systems Biology Assistant Professors Sagi Shapira, Peter Sims, and Harris Wang, along with the Genome Sequencing and Analysis Center of the JP Sulzberger Columbia Genome Center. The community is slated to grow, as currently unoccupied space will soon accommodate additional Columbia University faculty labs that are also developing new biotechnologies.

“Technology drives science,” says Department of Systems Biology Chair Andrea Califano, “and the ability to design new technologies can make it possible to answer questions that no one else can. By bringing technology-focused investigators and the Genome Center’s sequencing infrastructure together in the same physical location, our goal is that the new Lasker facility will give the Department of Systems Biology — and the entire Columbia University research community — access to unique applications for biological and biomedical research.”

New tools offer new opportunities

When Columbia University Medical Center launched the Columbia Initiative in Systems Biology (CISB) in 2010, an important part of its mission was to foster the integration of experimental and computational research methods. The Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics (C2B2) had already brought together scientists from across the University who shared an interest in studying biology from a quantitative perspective, but as the CISB evolved into the Department of Systems Biology it also expanded by hiring investigators who were working on powerful new technologies for high-throughput experimentation.

Among these hires was Harris Wang, a synthetic biologist who has invented several groundbreaking approaches for selectively reprogramming bacterial genomes. Because technological innovation is moving so quickly, he believes, it’s important for biological sciences departments to include not only basic scientists, but also other kinds of researchers who can develop new tools. “New technologies give you access to fundamentally new ways of looking at biological processes,” he explains. “By the time there’s a commercial kit to do something, a lot of the interesting questions have already been answered. The research communities that are going to be most successful are always the ones that are creating new applications, not just using what’s widely available.”

Also joining the new Department around that time was Peter Sims, a physical chemist by training who has been developing technologies that will make high-throughput sequencing of individual cells more efficient and cost-effective. Although his background is not that of a traditional biologist, his contributions to work in the Department of Systems Biology, the Columbia Genome Center, and elsewhere at Columbia University Medical Center are emblematic of the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration to recent biological research.

Since moving into his new laboratory in the Lasker Building (named for Mary Woodard Lasker, an activist and philanthropist who beginning in the 1940s played an essential role in rallying national support for cancer research), Dr. Sims has had the chance to expand, doubling the number of staff he can hire and adding instrumentation that he previously could not purchase because of space constraints. “The Cancer Center here at Columbia is great because it has so much advanced equipment and people are generally open to sharing it,” he says. “But in the past there were projects I couldn’t do because it would have been such an imposition on the people we were borrowing instruments from. Sometimes you just need to be a full-time user, and having more space gives us an opportunity to do that.”

Sharing the same laboratory space has also made it possible for the junior faculty to pool their resources, including an ultracentrifuge, tissue culture incubators, and other instrumentation. “In addition to sharing a certain sensibility,” Sims observes, “it’s turned out that our respective labs’ technical infrastructures are highly complementary. There’s been a lot of synergy we didn’t expect but that is already helping us all.”

Improved next-generation sequencing capabilities at the Columbia Genome Center

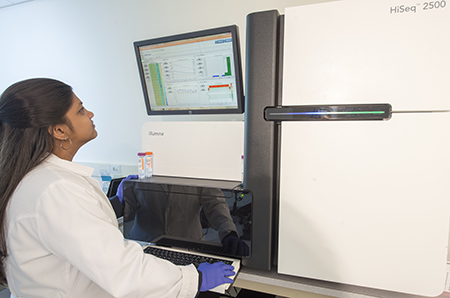

For the Columbia Genome Center, the move to a 2,000 square-foot space in the Lasker Building offers an opportunity to significantly expand its next-generation sequencing operations, including the potential to add larger instruments for sequencing genomes of large patient cohorts. The larger footprint also means that the Sequencing and Analysis Center’s wet lab and bioinformatics teams can now work in the same space, an arrangement that wasn’t possible in the past.

As next-generation sequencing continues to grow in importance to biomedical research, the Department of Systems Biology's expansion into Lasker is enabling an expansion of the Columbia Genome Center's Sequencing and Analysis Facility. Photo: Lynn Saville.

This expansion of the Genome Center’s sequencing capabilities reflects the steady growth in demand for high-quality genomic data over the past several years, particularly at the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer Center. (The Columbia Genome Center operates as a shared facility with HICCC.) As Genome Center Executive Director Olivier Couronne explains, “More than 120 different research groups have used our services over the past year, and our contributions have enabled the success of several National Institutes of Health-funded centers of excellence here at the university. The opportunity to expand the Genome Center’s operations in this way is a sign of the importance of genomics to the future of biological research at Columbia, particularly as its Precision Medicine Initiative continues to develop.”

Dr. Couronne also foresees ongoing innovation as an important component of the Genome Center’s future success. “To continue to be essential,” he remarks, “we must stay at the cutting edge of genomic science. This expansion into the Lasker Building will dramatically improve our ability to do this. Sharing the same floor with several laboratories that are doing such forward-thinking technology development will not only enable us to better support them but also help us to anticipate the future and to continue to evolve our capabilities.”

Promoting new collaborations

Ultimately it is these kinds of personal, cross-disciplinary interactions that the new Lasker facility aims to facilitate. Bringing technology-focused investigators into close physical proximity will enable conversations that will reveal new opportunities for collaboration, ultimately leading to new technical applications. In this way, it constitutes an important step in the evolution of the Department of Systems Biology.

For Sims, who also serves as Director for Novel Technologies at the Columbia Genome Center and uses its services frequently, the new arrangement has made it possible to interact with Genome Center staff more regularly and has made his experiments easier to implement. Since moving into their shared laboratory space in August, he and Dr. Wang have also already begun discussing new collaborations. Sims remarks, “It’s taken for granted that many of the older departments here at Columbia have contiguous floors, but at the time the Department of Systems Biology was founded that wasn’t physically possible. Now that’s changed, and there’s a huge difference between being in the same department as someone and seeing that person every day.”

In addition to its current occupancy, the new Lasker biotechnology hub also has a large allotment of laboratory space that remains to be distributed. Currently, discussions are underway between the Medical Center, the Department of Systems Biology, and other departments at the University about potentially incorporating other likeminded labs.

Future plans include moving the laboratory of Kam Leong to Lasker. A professor of biomedical engineering who recently became an interdisciplinary faculty member in the Department of Systems Biology, Dr. Leong has invented a variety of landmark nanoscale tools, including electrospun nanofibers, microfluidic platforms, and other technologies for delivering drugs, antigens, proteins, siRNA, and DNA to cells. As Dr. Califano explains, “Some of the technologies being developed in the Leong Lab and those of other investigators at Columbia University are highly relevant for addressing the kinds of questions that systems biology is exploring. We all realize that bringing some of these laboratories into closer proximity could lead to some exciting new science.”

Creating a facility that integrates faculties from systems biology and other departments will also facilitate better dialogue between Columbia University Medical Center and Columbia’s Morningside Heights campus, where several other basic science departments are located.

“I think it’s great that the Department of Systems Biology has been receptive to the idea of this kind of cross-departmental, technology-focused community,” Wang says, “because not all medical center departments are.” As the Lasker biotechnology hub continues to mature, everyone involved is looking forward to applying the new kinds of tools it promises to generate.

— Chris Williams