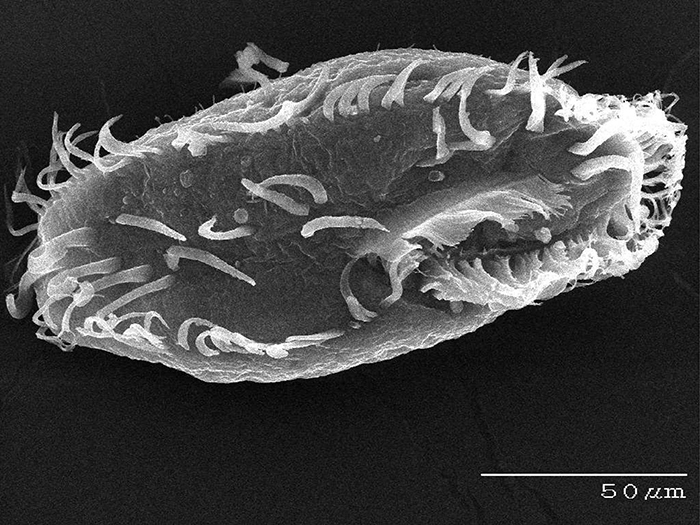

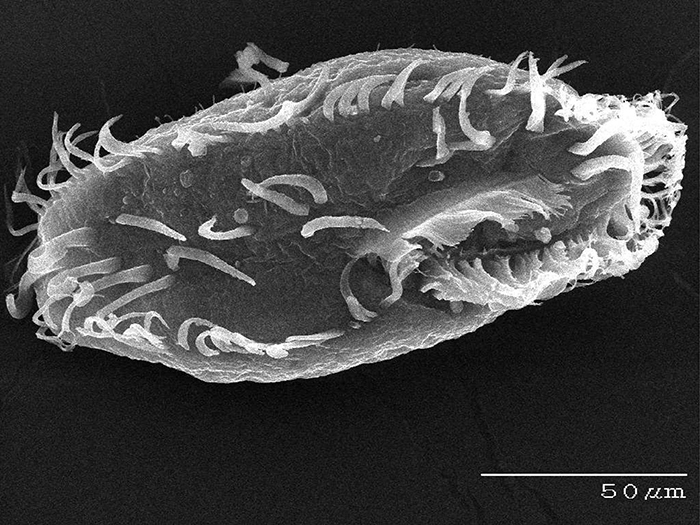

Oxytricha. (Credit: Bob Hammersmith)

Laura Landweber, PhD, loves a challenge. So it’s no surprise that she has built a scientific career unraveling the hows and whys of a unique single-cell organism known for its biological complexity.

An evolutionary biologist whose work sits at the interface of genetics and molecular biology, Dr. Landweber, for nearly 20 years, has focused much of her research on Oxytricha trifallax , a microbial organism that is prevalent in ponds, feeds on algae and has a highly complex genome architecture, making it an attractive, albeit challenging, model organism to study. Compared to humans, with 46 chromosomes containing some 25,000 genes, Oxytricha is known to comprise many thousands of chromosomes, in the ballpark of 16,000 tiny “nanochromosomes”. Yet not only is it complex in sheer numbers of chromosomes but the information carried in those individual chromosomes can be scrambled, like information compression, and the process of development in Oxytricha must descramble this information so that it can be converted into RNA and proteins.

“DNA can be flipped and inverted in Oxytricha and the cellular machinery actually knows how to restore order,” says Dr. Landweber. “Hence, it’s this wonderful paragon for understanding genome integrity and the maintenance and establishment of genome integrity.”

Even more perplexing, in cell division, Oxytricha reproduces asexually when it wants to produce more in number, and it reproduces sexually when it needs to rebuild its genome. It also has the ability to “clean up” its genome, so to speak, eliminating nearly all of the non-coding DNA, or so-called junk DNA. Much of why Oxytricha presents such an intricate genomic landscape remains a mystery, and for Dr. Landweber, the leading expert on this single-celled protist, that wide-open field for potential discovery is what got her hooked.