Reposted from the Columbia University Medical Center Newsroom. Find the original article here .

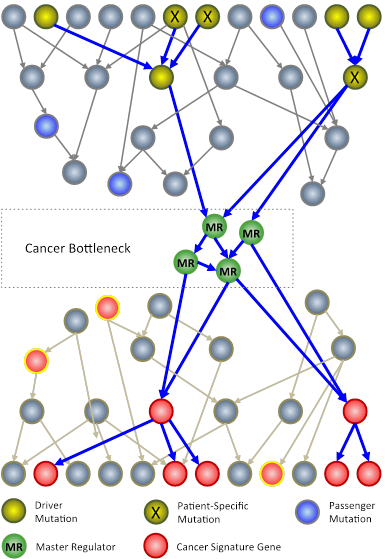

In an N-of-1 study, researchers at Columbia University use techniques from systems biology to analyze genomic information from an individual patient’s tumor. The goal is to identify key genes, called master regulators (green circles), which, while not mutated, are nonetheless necessary for the survival of cancer cells.

Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) researchers are developing a new approach to cancer clinical trials, in which therapies are designed and tested one patient at a time. The patient’s tumor is “reverse engineered” to determine its unique genetic characteristics and to identify existing U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs that may target them.

Rather than focusing on the usual mutated genes, only a very small number of which can be used to guide successful therapeutic strategies, the method analyzes the regulatory logic of the cell to identify genes and gene pairs that are critical for the survival of the tumor but are not critical for normal cells. FDA-approved drugs that inhibit these genes are then tested in a mouse model of the patient’s tumor and, if successful, considered as potential therapeutic agents for the patient — a journey from bedside to bench and back again that takes about six to nine months.

“We are taking a rather different approach to tailor therapy to the individual cancer patient,” said principal investigator Andrea Califano, PhD, Clyde and Helen Wu Professor of Chemical Systems Biology and chair of CUMC’s new Department of Systems Biology. “If we have learned one thing about this disease, it’s that it has tremendous heterogeneity both across patients and within individual patients. When we expect different patients with the same tumor subtype or different cells within the same tumor to respond the same way to a treatment, we make a huge simplification. Yet this is how clinical studies are currently conducted. To address this problem, we are trying to understand how tumors are regulated one at a time. Eventually, we hope to be able to treat patients not on an individual basis, but based on common vulnerabilities of the cancer cellular machinery, of which genetic mutations are only indirect evidence. Genetic alterations are clearly responsible for tumorigenesis but control points in molecular networks may be better therapeutic targets.”